|

Bishopstone, Sussex 1972 Oil on canvas 30.5 x 40.5 cm

This work is from a rather unsettled period in my life. I had lost confidence in my abstract work, and was doing quite a few small-scale figurative drawings and paintings, mainly landscapes. This painting was based on a black and white photograph and sketches I made on the spot, near my parents’ house at the time in Bishopstone, a village between Newhaven and Seaford on the south coast of England. The area in the foreground had been a cricket pitch, and the wooden building on the left the pavilion, now demolished. I seem to remember that there was a small hut, possibly a toilet, hidden in the large bush. I was interested in the formal contrast/connection between the pavilion, the bush, the sign in the distance, and the path through the long grass leading to the road climbing the hill on the right. But I was also trying to capture the atmosphere of the place, probably influenced by the paintings of Edward Hopper. I never finished the painting, but I like to think it has a certain atmosphere.

0 Comments

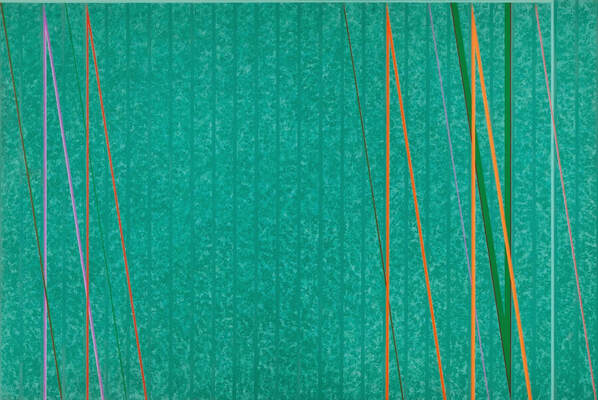

The Angela Flowers Gallery, London, 1973. The private view of a solo show by Colin Cina, a fellow student at the Central School of Art and Design. After graduating, Colin had built a reputation as an abstract painter and the show contained his latest work - very large paintings featuring vertical and diagonal lines of varying thicknesses and colours ranging across the canvas. Mike Leigh was a close friend of Colin's, and I had met him a couple of times in the 1960s when he was making a name for himself as a stage director. By 1973 he had made his first film, 'Bleak Moments', and was writing and directing for television. At the private view, I spotted him talking to a young man in front of one of Colin's huge paintings.

When I joined them, Mike was discussing the painting with the young man, who spoke with an unabashed upper-class drawl. "In fact," said Mike, "Colin's paintings are a kind of musical notation, and he wants the paintings not only to be enjoyed visually, but sung." "Sung?" "Yes, for example, that passage there could be …" Mike started humming, waving his arms to show how the lines and colours corresponded to his rhythm and melody. "Oh, I say, how fascinating!" cried the young man. He looked round the gallery, and beckoned to a middle-aged couple who turned out to be his parents. "Mummy, Daddy, you must come over here. This chap says the paintings can be sung!" Mummy and Daddy joined the group, and after a few minutes, Mike Leigh had the three of them singing lustily to the painting. I wonder if they bought it. P.S. Coincidentally, I came across this video on YouTube the other day. Episode 1: I was 17 years old and while waiting to enter the Central (School of Art and Design) had signed up for a weekly life drawing class at Tunbridge Wells art school. After a nervous bus-ride to my first session, my fantasies were dashed by that evening's model, a large middle-aged lady, and I soon realized that drawing a naked female body might have little to do with sexual attraction (although there would be exceptions later). Some of the models were fully clothed; after all, it was Tunbridge Wells. Episode 2: The following year I was a Central student, initially studying graphic design, then painting. Everyone was supposed to do life-drawing, but most of the students avoided it, considering it old-hat. Even though I was already exploring abstraction, I wanted to work on my representational drawing skills, and regularly attended the life-drawing sessions. The variety of models was fascinating and I remember another large middle-aged lady, who although quite happy to pose in front of a small group of art students, insisted that the tiny windows of the top-floor studio should be covered so that no office workers across the street would be able to get a glimpse of her. Episode 3: Quentin Crisp was an unforgettable model and made occasional appearances at the Central. He had been a fixture of the London art school scene for years, and would later become a celebrity when his autobiography 'The Naked Civil Servant' was published and made into a TV film. He had a very pale, almost marble-like body, wore a modest g-string and would assume poses based on Greek sculptures. He was a true professional and could hold a pose for an hour or so without budging an inch, but in the early 1960s that kind of pose was no longer 'cool', and attendance would drop noticeably on Quentin days. Coincidentally, I later met him a number of times when he lived on the floor below my then-girlfriend's place in Fulham and was honoured to enter his room, the contents of which were famously coated in thick dust. Episode 4:

One day, the few (mostly male) students were delighted to be faced with a young woman who apparently had never posed before. She was lovely, and I was smitten. I was looking forward to spending the whole day gazing at her in innocent (or so I thought) wonder and tried to think of some cool opening gambits. I never got the chance to try them out, as she felt unwell during the morning session and had to stop. I desperately wanted to step forward and say I would see her home, but was unable to work up the courage, and never saw her again. Episode 5: It started as an ordinary day with a few students dotted around the studio waiting by their easels or sitting on their donkeys. From the changing room stepped a young woman who, as she disrobed, became a vision from the Arabian Nights: seductive, honey-hued, wearing gold slippers and an ankle bracelet. There was a stunned silence, and after she had settled into her pose, we began to scribble nervously away. After the morning coffee break a few more students joined us. Then lunch, after which the life room was unusually full and all the easels and donkeys had been taken. Following the mid-afternoon break, students and lecturers from various departments (including committed abstractionists, textile artists, and industrial designers) were shoulder to shoulder, jostling for a good position. By the end of the day, to coin a phrase, the place was heaving. If you are wondering why I have no drawings to accompany the last two episodes, a lecturer lost my best work. It still hurts. *This was the title of a nudist film which was shown at the local fleapit when I was about 15. I was too young to get in, but spent some time ogling the stills outside. During a visit to Paris in September, I spent an afternoon wandering among the tombs and gravestones in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. Montparnasse Cemetery has its fair share of celebrated names (Sartre, de Beauvoir, Baudelaire, for example), but Père Lachaise holds a special attraction for anyone interested in French painting. I quickly fell into trainspotter mode, ticking off the names on my list of artists and writers. Armed with a downloadable map on my iPhone, some were easy to find (Delacroix, Géricault, Wilde, Proust), others less so; the Pissarro family grave is tucked away in a corner and Ingres is modestly placed behind other tombs. I'm not sure why I felt the need to find the graves and read the names; perhaps it was simply a tourist's impulse to 'do the sights'. As well as being a historical record, any cemetery encourages thoughts about life and death. But at least for me, Père Lachaise added a powerful sense of an artistic tradition. "When you're in the studio painting, there are a lot of people in there with you - your teachers, friends, painters from history, critics ... and one by one if you're really painting, they walk out. And if you're really painting, YOU walk out."

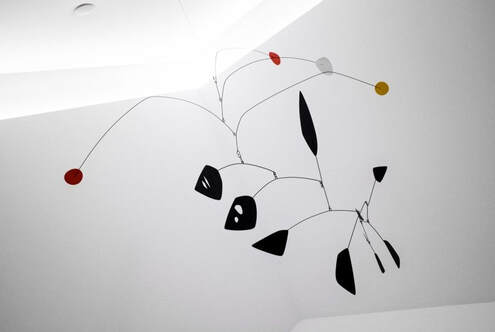

Last summer I was visiting my brother in Somerset. After a pub lunch he suggested going to the Hauser and Wirth gallery on the outskirts of Bruton, just a short drive away. I'd heard about the place, which seemed to be a kind of hip outpost of the London operation in the depths of the West Country, and read how property prices had risen dramatically in the village after the gallery opened.

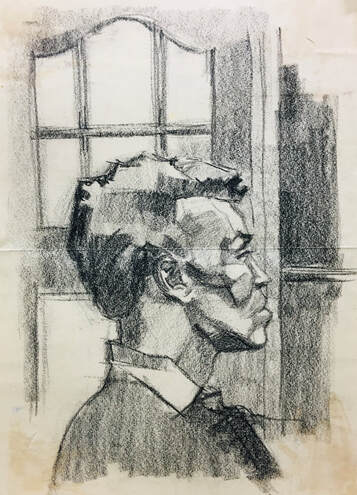

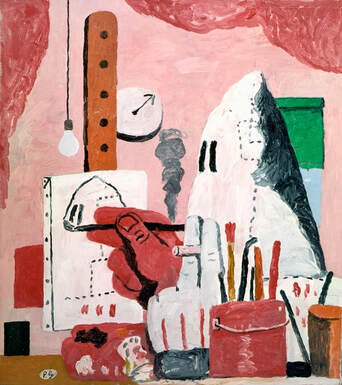

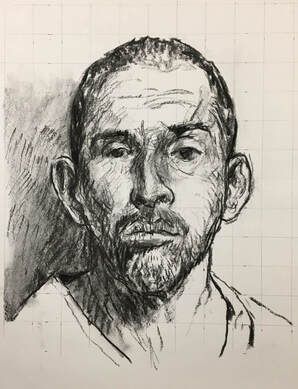

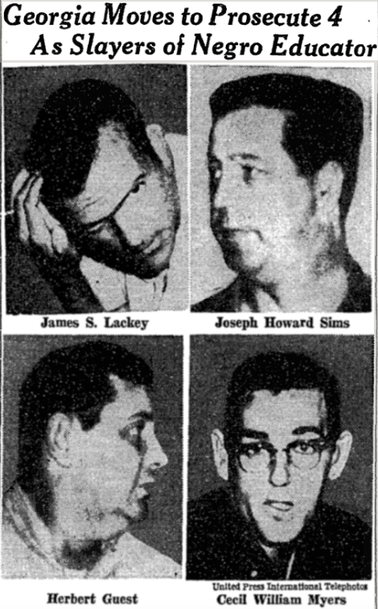

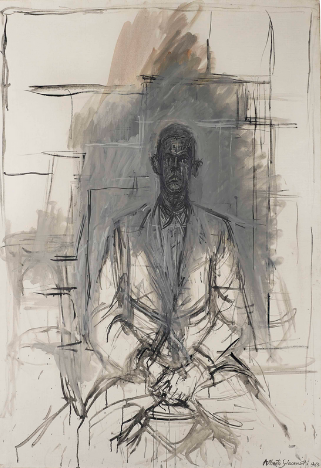

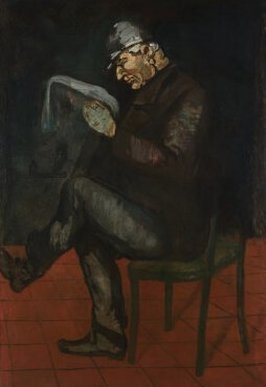

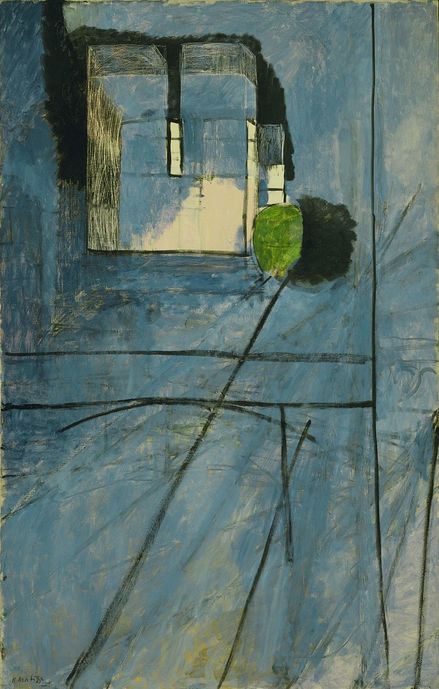

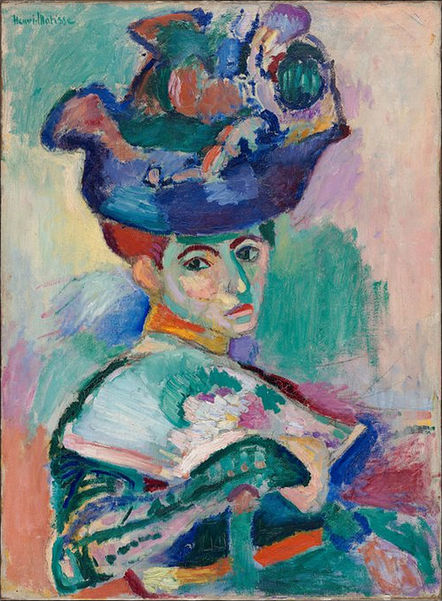

The current show was a small Alexander Calder retrospective. My brother had already seen it and hadn't been impressed with the show or the gallery, and he wanted to see what I thought of it. I'd always liked Calder's work, so I was looking forward to a healthy argument as we wandered round. For some reason I wasn't impressed either. This could well have been a result of my increasing dislike of exclusive high-end galleries, and the realization that I seemed to be much older and definitely less cool than the other visitors. I didn't think much of the paintings. The stabiles were OK. But I did really like some of the mobiles. I've always liked the idea of mobiles, and when I was teaching art in a comprehensive school in the 1960s, a mobile-making project was always a surefire hit with the kids. A particularly large mobile in the corner of one room attracted me. But there was a problem. Like all the others in the show, this mobile was completely static, and one thing a mobile should do is to move, even if very slightly and very gently. So from a respectable distance I blew on the tip of one branch. It barely moved. I blew again, a little harder, and it very gently wafted away. It looked good. I felt a tap on my shoulder. "No blowing," said a frowning attendant. "But it's a mobile," I said. "Mobiles are supposed to move. That's the whole point." "No blowing," she repeated, wagging her finger. I was caught between childish guilt and geriatric anger. "Can I suck?" I said. She walked away, still frowning. So never blow on a Calder. A few years ago I discovered the website www.mugshots.com, and marvelled at the portraits it contains. Frontal and unsmiling, they are accompanied by a brief account of a crime or crimes. While reminiscent of the earlier giant portraits by Chuck Close, they are far from being deadpan and a vehicle for a formal exercise, and suggest a narrative of turbulent and often violent life stories. Earlier this month I came across a number of mugshots I had saved from the website on my desktop a few years ago. I started making large drawings in charcoal, and found the process to be quite unsettling. Simply by concentrating on and interpreting the image, the individual seemed to emerge into my space in a slightly disconcerting way. The drawings (I hope) suggest stories and elicit emotions. Does this mean they are illustrations, or 'kitsch' in the sense that Odd Nerdrum has defined the word (non-ironic, 'sentimental', emotional). All I know about J.L. in the drawing above is that he was arrested for first degree murder: stabbing an older man in an 'alcohol-fueled argument regarding a woman'. Whatever he did, my aim was to make the drawing non-judgmental, to present him as a person who has clearly had many problems, and probably few chances to escape them. The mugshots reminded me of a large work of mine from 1964 (long since disappeared), painted in my second year in fine art at the Central* and based on a small newspaper photograph of four American Ku Klux Klansmen who had been charged with the murder of Lemuel Penn, an African American, in Georgia. I remember that I used mainly reds and greens (complementary colours to heighten the drama, probably) and a fairly traditional free painterly style on unprimed canvas. I was quite excited about the possibilities of a fresh approach to figuration and worked on it for a couple of days in the second-year communal studio. During the third morning I was applying some finishing touches when the doors of the studio burst open and in strode a group of three lecturers, including the head of department, who was clearly very angry. "This is not painting! This is illustration!" he spluttered, and stormed out. I was so surprised I was unable to say a word in my defence. At the time, the approved manner of painting at the Central was abstract or semi-abstract, and the idea of making a figurative image from a photograph was anathema. Did I continue in that style? Maybe for a while (uncowed, I like to think), but a year later I was making large paintings which were a combination of, in my mind at least, Monet and Rothko. These led to an interest in Op Art, and the paintings I made at the end of my final year brought me a small amount of recognition in the London art world, and with it, the beaming approval of the head of department. I had forgotten the details of the 1964 murder but a lengthy Google search led me to the New York Times Timesmachine archive page, where I eventually found the original photograph. At first I only clearly recalled the face of Cecil William Myers (bottom right), but the others have gradually become more familiar the longer I look at them. According to Wikipedia, the KKK members were found not guilty of murder by an all-white jury, but were successfully prosecuted two weeks later under the newly-introduced Civil Rights Act of 'violating Penn's civil rights'. Sims and Myers were sentenced to prison terms of ten years and served about six. Their co-defendants were found not guilty. (*The Central School of Art and Design, now Central St Martins) In 2017, I visited the Giacometti exhibition at the National Art Museum in Tokyo. The show concentrated on the sculpture, but there were also a number of drawings, which I loved, and a couple of paintings. The overall impression was of an artist wrestling with the questions of reality and perception. There were no answers, but the sculptures were impressive, and to use a hackneyed term, timeless. Although I was familiar with Giacometti's painted portraits from collections, previous exhibitions (including the 1965 show at London's Tate Gallery), and reproductions, I found that the paintings still puzzled me in ways the sculptures and the drawings did not. I recently watched the movie 'The Final Portrait' with Geoffrey Rush as Giacometti. The film, which I thoroughly enjoyed, led me to read 'A Giacometti Portrait' by James Lord, a short account of Lord's experience of sitting for the artist, and on which the film was based. Giacometti's single-mindedness and constant doubt fascinated me. I then read Lord's biography of the artist, looked at numerous reproductions, and watched as many Giacometti-related videos on YouTube as I could find. Giacometti said that he was trying to paint what he saw and was destined to fail. In a 2016 post, I wrote about the concept of artistic failure and quoted Giacometti: “All I can do will only ever be a faint image of what I see and my success will always be less than my failure or perhaps equal to the failure.” Even though the painted portraits may bear a likeness to the sitters, it is reasonable to assume that the paintings do not closely resemble what was in front of him. Of course, any artist's paintings are interpretations of what is seen, but somehow Giacometti's works seem to consist entirely of the process of interpretation. They are records or traces of how he saw –measuring, adjusting, readjusting, erasing. Colour is virtually absent, as if it would hinder the realization of the solid form of a head or body. In terms of form, his drawings are generally much closer to 'reality' than the paintings. So did the act of painting present particular problems of technique? Or did the paintings attempt something more ambitious, and therefore more difficult? Giacometti's painting can be seen as an extension of the late work of Cézanne (who he greatly admired), but a major difference is the virtual abolition of color in Giacometti's paintings. Even so, there is a clear connection between a typical Giacometti portrait and, say, Cézanne's late frontal portraits of his gardener, Vallier. And is it too much of a stretch to see a connection between Giacometti's mainly monochromatic images and the idea that nothing in the world 'out there' has intrinsic color? The notion that the world is full of colorless objects waiting to be brought to life by the perception of the onlooker? In my secondary school art class in 1961, we were told to make a linocut on the topic of 'Concentration'. This was my effort, which my brother Frank rechristened 'Constipation'. I recently realized it has something in common with Cézanne's early 'The Painter's Father', now in the National Gallery. Matisse painted View of Notre Dame in 1914. More than a hundred years later it's still a challenging painting. I'm still slightly disconcerted by the way it's painted. I feel an urge to tidy it up a bit, but I know that would be absurd. This painting is possibly the first 'finished' work in the history of western art to blatantly display the way it was built up, and the pentimenti are crucial. The Moma website claims that Matisse "left early compositional elements visible beneath the paint, accentuating the temporal quality of building a work of art over time." I doubt that was his intention; it's more likely that he left the compositional elements visible simply because it would have been somehow dishonest to completely erase them. After seeing the painting in Matisse's studio, the critic Marcel Sembat described it as "lopsided; no one would understand [it] immediately." In fact, Matisse didn't show the painting until 1949, when it was thought to be "an unfinished sketch to which Matisse had unaccountably signed his name." In fact, a 'rough' or 'unfinished' quality was characteristic of Matisse's work of the period. We tend to scoff at viewers who were shocked by the early Fauve paintings such as Woman with a Hat of 1905; Leo Stein, the brother of Gertrude, thought the painting was "the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen," but bought it nevertheless, recognizing its power. View of Notre Dame shows the view from the window of his Left Bank apartment, a scene that Matisse knew well and had painted many times before. Two diagonal lines denote the Seine and the Quai and lead the eye past the horizontals and curved line of the Petit Pont to a green tree and its shadow, then to the mass of Notre Dame, which has clearly increased in size. A vertical line on the right suggests the window frame. Apart from that there is basically a whole area of a modulated pale blue, becoming darker towards the top left-hand corner. A suggestion of ochre at the bottom. All very roughly brushed in or scraped with a palette knife. As with many works by Matisse, there is little hint of the lovingly crafted surfaces and textures that would typify later French abstract painting. As with Woman with a Hat, we can never quite relax; we are constantly assessing and re-assesssing what we are seeing. And we realize that every mark, even an apparently haphazard area of scratching, is in fact intentional and plays a vital part in the whole composition. During the period 1913-17, the period of 'radical invention', we feel that Matisse was never simply repeating something he had done before; each work, and each decision within a work, was testing the limits of painting. It's possible that this and other paintings of the same period were Matisse's response to Cubism. Picasso commented that Matisse never understood Cubism; maybe it was true that Matisse didn't understand the analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque. That wouldn't be surprising, as for Matisse, colour always played a major role, and early Cubism was unapologetically brown and grey. Also, Picasso's Cubist works tended to be representations of three-dimensional objects in space, however fractured and distorted. In contrast, Matisse would always treat every part of the canvas on equal terms. His love of flatness, pattern, and colour meant that he could not be bound by the rules of analytical Cubism. View of Notre Dame takes the contrast between the flatness of the picture plane and the implied depth of the scene to extreme lengths, and this presaged the work of the 'classic' abstract expressionists such as Robert Motherwell, and younger artists such as Richard Diebenkorn. Matisse's period of experimentation would end in 1917, and he would only return to a similar flatness in the last twenty years of his life, most notably in the paper cut-outs. Possibly, even for him, the stress of maintaining such an uncompromising mode of representation was too much to maintain for long. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed