|

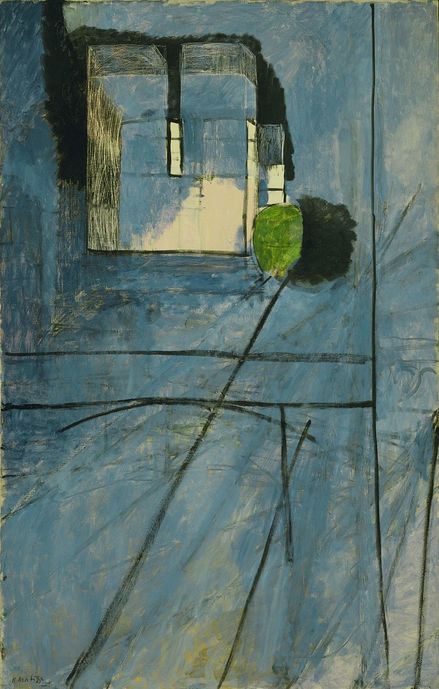

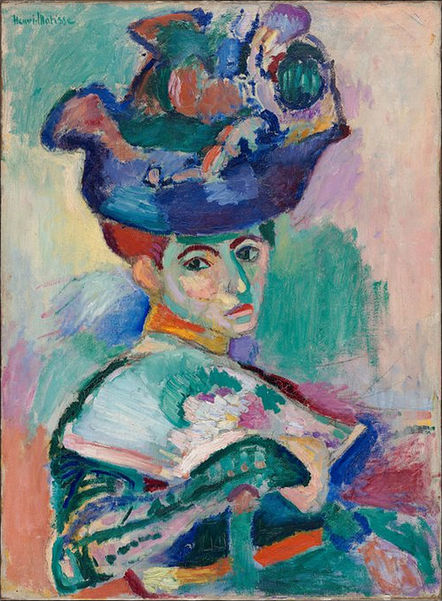

Matisse painted View of Notre Dame in 1914. More than a hundred years later it's still a challenging painting. I'm still slightly disconcerted by the way it's painted. I feel an urge to tidy it up a bit, but I know that would be absurd. This painting is possibly the first 'finished' work in the history of western art to blatantly display the way it was built up, and the pentimenti are crucial. The Moma website claims that Matisse "left early compositional elements visible beneath the paint, accentuating the temporal quality of building a work of art over time." I doubt that was his intention; it's more likely that he left the compositional elements visible simply because it would have been somehow dishonest to completely erase them. After seeing the painting in Matisse's studio, the critic Marcel Sembat described it as "lopsided; no one would understand [it] immediately." In fact, Matisse didn't show the painting until 1949, when it was thought to be "an unfinished sketch to which Matisse had unaccountably signed his name." In fact, a 'rough' or 'unfinished' quality was characteristic of Matisse's work of the period. We tend to scoff at viewers who were shocked by the early Fauve paintings such as Woman with a Hat of 1905; Leo Stein, the brother of Gertrude, thought the painting was "the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen," but bought it nevertheless, recognizing its power. View of Notre Dame shows the view from the window of his Left Bank apartment, a scene that Matisse knew well and had painted many times before. Two diagonal lines denote the Seine and the Quai and lead the eye past the horizontals and curved line of the Petit Pont to a green tree and its shadow, then to the mass of Notre Dame, which has clearly increased in size. A vertical line on the right suggests the window frame. Apart from that there is basically a whole area of a modulated pale blue, becoming darker towards the top left-hand corner. A suggestion of ochre at the bottom. All very roughly brushed in or scraped with a palette knife. As with many works by Matisse, there is little hint of the lovingly crafted surfaces and textures that would typify later French abstract painting. As with Woman with a Hat, we can never quite relax; we are constantly assessing and re-assesssing what we are seeing. And we realize that every mark, even an apparently haphazard area of scratching, is in fact intentional and plays a vital part in the whole composition. During the period 1913-17, the period of 'radical invention', we feel that Matisse was never simply repeating something he had done before; each work, and each decision within a work, was testing the limits of painting. It's possible that this and other paintings of the same period were Matisse's response to Cubism. Picasso commented that Matisse never understood Cubism; maybe it was true that Matisse didn't understand the analytical Cubism of Picasso and Braque. That wouldn't be surprising, as for Matisse, colour always played a major role, and early Cubism was unapologetically brown and grey. Also, Picasso's Cubist works tended to be representations of three-dimensional objects in space, however fractured and distorted. In contrast, Matisse would always treat every part of the canvas on equal terms. His love of flatness, pattern, and colour meant that he could not be bound by the rules of analytical Cubism. View of Notre Dame takes the contrast between the flatness of the picture plane and the implied depth of the scene to extreme lengths, and this presaged the work of the 'classic' abstract expressionists such as Robert Motherwell, and younger artists such as Richard Diebenkorn. Matisse's period of experimentation would end in 1917, and he would only return to a similar flatness in the last twenty years of his life, most notably in the paper cut-outs. Possibly, even for him, the stress of maintaining such an uncompromising mode of representation was too much to maintain for long.

4 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed