|

Last summer I was visiting my brother in Somerset. After a pub lunch he suggested going to the Hauser and Wirth gallery on the outskirts of Bruton, just a short drive away. I'd heard about the place, which seemed to be a kind of hip outpost of the London operation in the depths of the West Country, and read how property prices had risen dramatically in the village after the gallery opened.

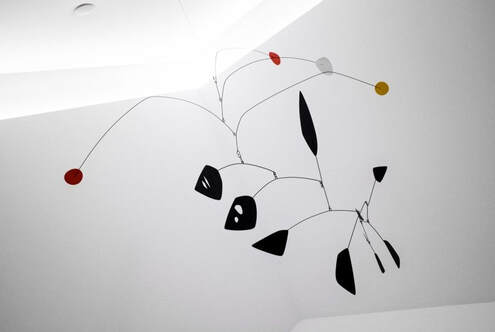

The current show was a small Alexander Calder retrospective. My brother had already seen it and hadn't been impressed with the show or the gallery, and he wanted to see what I thought of it. I'd always liked Calder's work, so I was looking forward to a healthy argument as we wandered round. For some reason I wasn't impressed either. This could well have been a result of my increasing dislike of exclusive high-end galleries, and the realization that I seemed to be much older and definitely less cool than the other visitors. I didn't think much of the paintings. The stabiles were OK. But I did really like some of the mobiles. I've always liked the idea of mobiles, and when I was teaching art in a comprehensive school in the 1960s, a mobile-making project was always a surefire hit with the kids. A particularly large mobile in the corner of one room attracted me. But there was a problem. Like all the others in the show, this mobile was completely static, and one thing a mobile should do is to move, even if very slightly and very gently. So from a respectable distance I blew on the tip of one branch. It barely moved. I blew again, a little harder, and it very gently wafted away. It looked good. I felt a tap on my shoulder. "No blowing," said a frowning attendant. "But it's a mobile," I said. "Mobiles are supposed to move. That's the whole point." "No blowing," she repeated, wagging her finger. I was caught between childish guilt and geriatric anger. "Can I suck?" I said. She walked away, still frowning. So never blow on a Calder.

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed